|

|

300% - 700% Premium Paid for Non-GMO...

Uphill Struggle for Hawaii's Biotech Papayas  (27 April - Cropchoice News) -- A biotech fruit that developers said "could save the entire Hawaiian papaya industry" is instead running into serious marketing problems. (27 April - Cropchoice News) -- A biotech fruit that developers said "could save the entire Hawaiian papaya industry" is instead running into serious marketing problems.

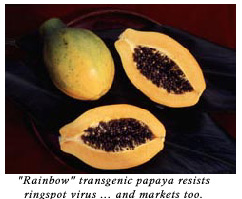

Two GMO papaya varieties released in 1998, "Rainbow" and "SunUp", have been rejected by foreign buyers. It's a big deal in Hawaii, whose firm, quality fruit grown on rocky volcanic soil is in demand in export markets like Japan, Canada, and Europe. Japanese exports alone account for 40% of Hawaii's fresh papaya market.

The papayas were developed the University of Hawaii, Cornell, USDA, and Monsanto to resist ringspot virus, a serious disease that is taking a heavy toll on growers. The aphid-carried ringspot was bad enough on parts of the Big Island (where most of Hawaii's papaya is grown), that farmers had abandoned fields. Because of the heavy virus pressure, production had taken a downturn of over 40%.

The biotech plants were first sown commercially in 1998 and, according to industry, were a stunning biotech success. Hendrik Verfaillie, President and COO of Monsanto, told Congress last year that thanks to Monsanto biotechnolgy "Now, this industry, made-up mostly of small growers and once on the verge of extinction, is flourishing."

But Monsanto may have spoken too soon. Papayas take 18 months to grow to maturity and full scale marketing of the GMO varieties has only recently started.

So far, farmers don't have many complaints about the field performance of the biotech papayas. SunUp, the red fruit variety, has had no resistance breakdowns. Rainbow, an orange fruited hybrid, has good disease resistance, although some young plants and, according to some sources, some adult have shown susceptibility. Rainbow's developer's, however, dispute the reports of resistance breakdown.

The major problem with the biotech fruit is marketing. Hawaii went GMO without anticipating the market. According to Mike Durkan, a grower in Keaau, SunUp has performed well in the field; but terribly at market. "It's better than nothing," says Durkan, "with SunUp I have a stable production." But he has decided to sacrifice the resistance and move to non-GMO varieties.

Durkan explains "I'm not planting SunUp now. I'd really like to sell to the Canadian market ... there I'm looking at 3 or 4 times the profit." While biotech papayas run between 20 and 30 cents a pound, Canadian buyers are paying 45 cents for non-GMO varieties. A few months ago, the price paid by Japanese buyers for non-GMO spiked up to 60 cents a pound. With costs of production at about a 25 cents, farmers are getting a 300% - 700% premium on non-GMO fruit.

The issue is a tough one for state officials. Last year, they convinced the Hawaii Legislature to approve a special appropriation to pay for the costs of patent licensing for SunUp and Rainbow. Hawaii officials had to make arrangements with several research groups, including a deal with Monsanto, which holds a patent on a key virus gene.

But the with the marketing problems, the State Bureau of Agriculture appears to be doubling back. James Nakatani, the Bureau's head, told the Hawaii Tribune-Herald that foreign buyers' refusal to accept GMO fruit gave growers "an impetus ... to get the (non genetically-engineered) Kapoho Solo variety back to its place of prominence".

According to Durkan, non-GMO company farms in the Philippines are benefitting from Hawaii's reduced ability to give Japanese and Canadian consumers what they want. "They're buying from Dole down in Mindanao," says Durkan. It's tough situation for Hawaiian papaya farmers, who are almost all small producers. They're now facing tough international competition with a big company that wants to capitalize on the non-GMO market.

Debate in Hawaii is focusing on how to implement a new virus containment program. Earlier efforts failed. In order to reduce virus pressure, some officials are proposing to cut down several hundred acres of infected trees. Farmers want compensation for any losses. Depending on how the program is implemented, in the short-term, this may create pressure on farmers to plant GMO varieties (or not plant at all), although ultimately, reducing virus pressure will create more promising conditions for varieties like Kapoho Solo.

Farmers are pressing the state to provide good up-front compensation for farmers. If farmers like Durkan get their way, a containment program will be implemented that will reduce virus pressure while protecting important and profitable export markets.

SOURCES: Hawaii Tribune-Herald, Cornell University, Monsanto, Mike Durkan.

|